By Robert Moor

We live among creatures far taller, far stranger, and far, far more long-lived than any dinosaur. Beings whose life spans can be counted in millennia and in whose shade entire empires crest and crash.

It seems no accident that children, who are accustomed to looking upward to perceive the world, are the world's great dinophiles and arborphiles. In young adulthood, we tend to lose that uptilted cast of the eyes, that awe for the awesome. But some of us, by accident or force of will, are lucky enough to regain it.

Beth Moon followed just such a trajectory. A field-roaming, tree-climbing child, she grew up to find she was spending most of her days indoors, working as an artist and designer. Then, in her forties, for reasons she still can't quite fathom, she began photographing old trees in her neighborhood. The results were unimpressive, but she persisted.

Her photos only flared to life when she locked in on what fascinated her most: the relationship between trees and time. Time, in Moon's mind, is a roil rather than a laminar flow. "Dates feel meaningless to me," she confesses. She loves the way that trees hold time, clutching it to themselves in concentric rings, recording the feast or famine of each season. Several years ago, construction workers in New Zealand accidentally unearthed the partially fossilized trunk of a kauri tree that had died 42,000 years earlier. Its rings, spanning 1,700 years, captured radioactive evidence of the last time Earth's magnetic poles flipped.

Joshua tree • Yucca brevifolia • Mojave Desert, United States

Because Joshua trees don't have rings, it's difficult to pinpoint their age. Instead, age is estimated by size. The average life span is 150 years, but one yucca (they're technically not trees) in

Joshua Tree National Park is believed to be over 1,000 years old.

Beth Moon | Joshua Tree | Platinum/palladium print

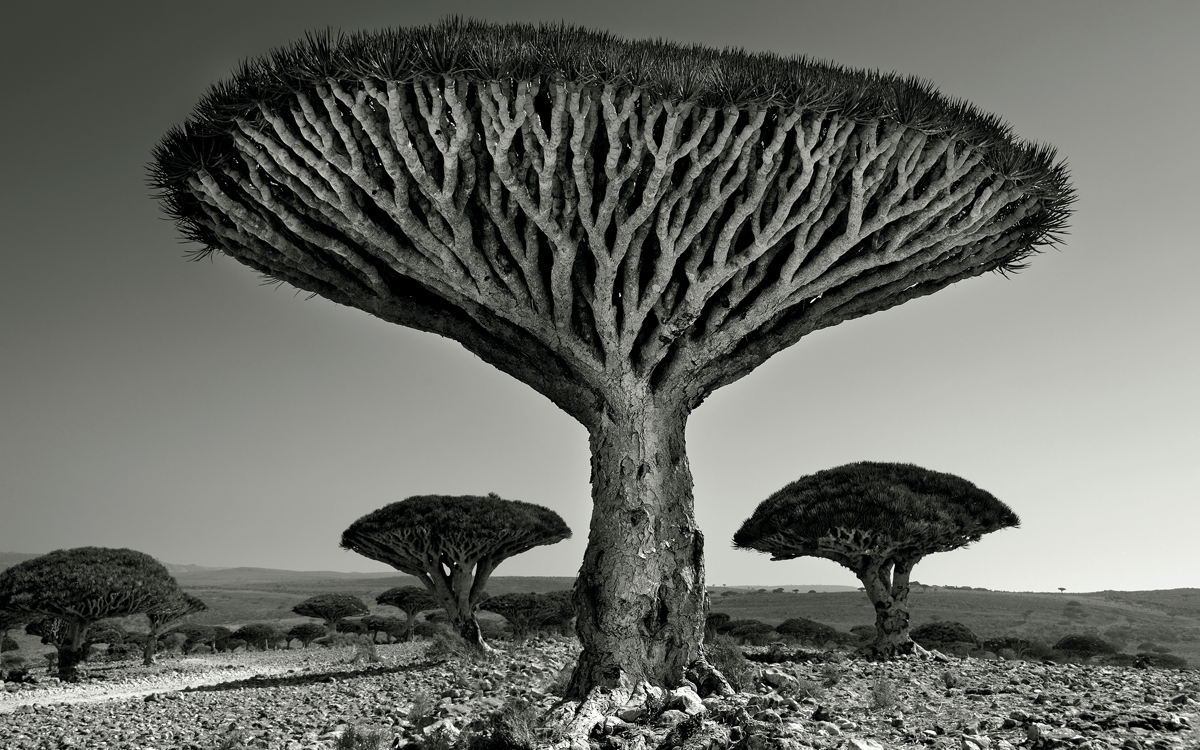

In the 1990s, Moon, who was then living in England, began seeking out old trees, driving farther and farther afield. When she moved to California in 1999, she discovered a "feast" of ancients—giant redwoods and bristlecone pines (some more than 4,000 years old). She widened her gaze further: to Italy, Cambodia, Senegal, Namibia, Madagascar. In Yemen, she camped out on an island called Socotra, home of the so-called dragon blood trees—great, mushroom-shaped oddities that bleed ruby-colored resin.

Moon wields time as a tool. She typically photographs a tree over many sessions, ideally over several days. Developing and printing is a days-long process, in which a solution of platinum and palladium is hand-brushed onto paper and then exposed. (Her preferred paper, which is made of cotton, has been produced by the same mill in France since 1492.) The platinum lends a luminous quality to the leaves—an echo of their function, to eat sunlight—and a leaden, indestructible weight to the trunks.

While most plants possess a genetically circumscribed life span (what biologists call senescence), many trees barely seem to age at all. "That trait—indefinite growth—could be science's tidiest demarcation of tree-ness," science writer Rachel Ehrenberg notes. When Moon began seeking out the oldest trees, 20-plus years ago, she believed they were nearly immortal.

That is no longer the case. "The oldest trees are dying," Moon says. "It's kind of breaking my heart." The changing global climate has led to a cruel combination of drought and pestilence. The 1,000-year-old olive trees she photographed in Puglia in 2015 are almost all dead now, owing to a pathogen called Xylella fastidiosa. The habitat of dragon blood trees shrinks every year. Even sequoias, the most massive and well defended of all trees, are now being weakened by drought, fire, and bark beetles.

In 2019, Moon heard that one of the trees she had photographed, the largest baobab in Madagascar, had split in half, lengthwise. (The standing half was still alive but wouldn't be for long.) She embarked on a pilgrimage to see it one last time. During the last leg of the journey, the island, which had been stricken by drought for the previous three years, was suddenly lashed with heavy rains. The road to the big tree was flooded, so Moon, riding in a cart pulled by a team of zebu, was forced to detour. Along the way, she was surprised to discover a number of giant trees that she would have never seen otherwise. "So in a way, the trip was about saying goodbye to this tree," she says. "But it was also about celebrating the beauty of the trees that still remain." —Robert Moor

English oak • Quercus robur • Kent, England

In Nonington, one of the largest maiden oaks in Europe is estimated to have begun growing during the Elizabethan era. "Maiden" means that the tree has never been pollarded or trimmed

in order to give its branches a more manicured appearance.

Beth Moon | Majesty (back) | Platinum/palladium print

Olive tree • Olea europaea • Puglia, Italy

Puglia is home to the highest concentration of ancient olive trees in the world. The oldest have been here for over 1,000 years.

Beth Moon | Olive Tree | Platinum/palladium print

Dragon blood tree • Dracaena cinnabari • Socotra, Yemen

Dragon blood trees are unique to the island of Socotra. Once part of a vast forest, the remaining trees—some of which are 500 years old—are now classified as vulnerable to extinction.

Beth Moon | Shebehon Forest | Platinum/palladium print

Yew tree • Taxus baccata • East Lothian, Scotland

This yew, with its massive, 11-foot-diameter trunk, is estimated to be nearly 1,000 years old. It is said that in 1567, a group of Scottish nobles met in the shelter of the tree to plot the murder

of Lord Darnley, the husband of Mary, Queen of Scots.

Beth Moon | The Whittinghame Yew | Platinum/palladium print

Baobab tree • Adansonia grandidieri • Morondava, Madagascar

In Madagascar, the baobab is called renala, or "mother of the forest," in Malagasy; these baobabs can grow to nearly 100 feet in height and live past 800 years old. Once part of a dense

tropical forest, they are now threatened by agricultural expansion and climate disruption.

Beth Moon | Avenue of the Baobabs | Platinum / Palladium print

English oak • Quercus robur • Oxfordshire, England

Grand old trees that dominate their surroundings are sometimes called "wolf trees." This term was likely inspired by the predatory nature of large trees whose wide, spreading crowns

inhibit the growth of smaller trees around them.

Beth Moon | English Oak | Platinum/palladium print

Beth Moon is a California-based photographer who has gained international recognition for her large-scale, richly toned prints. Her work has appeared in more than 75 solo and group exhibitions worldwide.

This article appeared in the Summer quarterly edition with the headline "Time Travelers."