by Maria Porges

The Japanese word sodachi describes the importance of the place you were born and raised and its influence on your taste, character and path in life. Photographer Michael Kenna has said that his solitary boyhood in a small British industrial town, wandering through deserted places, had a greater influence on his work than his art school education.

His pictures are known for a lack of people — even when they are the putative subject, as in his series on German concentration camp sites or a kindergarten classroom in San Francisco. Viewing one of his exhibitions allows one to imagine the world after the catastrophic disappearance of humanity. There is evidence of civilization: fences, roads, manicured trees or shrubs, terraced hillsides and stone temples. In these somber images, shot at night or in the first light of dawn, there is only landscape — groves of trees, views over water of distant shores — offered up without interruption, in perfect compositions of black, white and all shades of gray.

Michael Kenna | Montecito Garden, Study 13, California, 2006 | Silver gelatin print | 7.5 x 7.5 inches

The small, handsome pictures in Kenna’s current show at Dolby Chadwick, Holga and Recent Prints, demonstrate his gifts for composition and his technical prowess, both during and after shooting. Kenna prints all of his work himself, controlling the effects of light on the photographic paper in the darkroom. He is clearly a master of black–and–white film photography: an art form that, in the digital present, could be seen as quaint or archaic. Still, like painting’s much-vaunted demise, reports of analog photography’s extinction might be premature, judging by the robust market for both historical and contemporary prints, as well as the substantial number of young artists who have been drawn to work with all kinds of old-fashioned processes.

The perfection of Kenna’s work is exemplary. It carries a lustrous uniformity, which is all to the good, but it can sometimes be exhausting. A line of trees along a road, for example, looks pretty much the same wherever you shoot it. After 40-plus years of work, this is not surprising.

Still, Kenna has found a way to step back from his own expertise and at least intermittently keep the process somewhat unpredictable. The works in Dolby Chadwick’s main gallery were shot with Hasselblad view cameras that he carries in a backpack on trips to such places as Italy, Spain, Laos, Tasmania, China, South Korea, Japan, and various sites across the US. Recently, though, Kenna has begun using a second type of camera: a Holga, with which he has been taking a few pictures wherever he goes.

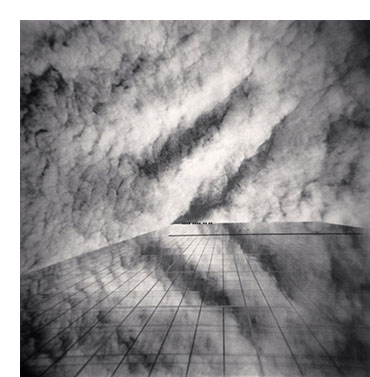

Michael Kenna | Skyscraper and Clouds, New York, New York, 2016, (6/25) | Silver gelatin print | 7.5 x 7.5 inches

In the smaller second room, there are several of these on view, recently released a book, Holga (Prestel, 2018).

The Holga is essentially a toy, originally made in Hong Kong in the 1980s for a mass market. Its simple plastic lens and cheap construction result in a host of accidental effects — vignetting (dark shadows around the periphery of the image), blur, light leaks, distortions. Even for someone as skilled and experienced as Kenna, the camera still yields surprises. He has four or five of them, and “each one has a different characteristic,” says the artist. “They’re not machine-built to the point they’re consistent, so you really don’t know what you’re getting ahead of time.” In other words, some shots that he was sure would be great were not, whereas others were startlingly engaging when he got the negatives back from processing.

The allure of such surprises is obvious. What is fascinating is the extent to which, once one becomes accustomed to the shadowy ring around the perimeter of these pictures, or their stark contrasts, Kenna’s expert eye creates compositions that are identifiably his. The subjects are the same: plants, water and trees. No people, just buildings and trees; graceful, elegant silhouettes.

Michael Kenna | Ai, Study 2, 2012, | Silver gelatin print | 8.25 x 7.75 inches

In the main gallery, there is a single startling example of a very different body of work. On a trip to Japan a decade ago, Kenna began setting aside time to shoot semi-abstract female nudes, picturing them in stereotypically traditional Japanese interiors: dark wood, tatami mats, shoji screens (even, in one picture, a strategically-placed parasol). Ai, Study 2 (2012), is an outlier among outliers, featuring a reflection of the model's limbs in a highly polished tabletop. We see four legs, three and a half arms and a paper light fixture doubled to suggest something resembling a letter or character. Other Kenna nudes, found on the Internet, recall works by Ruth Bernhard, for whom Kenna printed pictures for several years in the 1970s and 1980s.

Aside from this single peculiar departure from his usual landscape subjects, there is a lot to enjoy in the myriad scenes on view here—the colonnades of graceful trees, long night exposures of shore and sky. It’s not his fault that a number of these now look like greeting cards — his work has generated such a mass of followers that a demand for Kenna-like pictures has proliferated. I found myself thinking of that odd picture of disembodied limbs as another way that the artist, a one-time seminarian who spent most of his teenage years training for the Catholic priesthood, is trying something outside the box. For me, his work with the Holga has yielded far more compelling results.

# # #

Michael Kenna: Holga and Recent Prints @ Dolby Chadwick Gallery through February 23, 2019.