by Voyage Chicago Staff

Today we’d like to introduce you to Louise LeBourgeois.

Louise, please share your story with us. How did you get to where you are today?

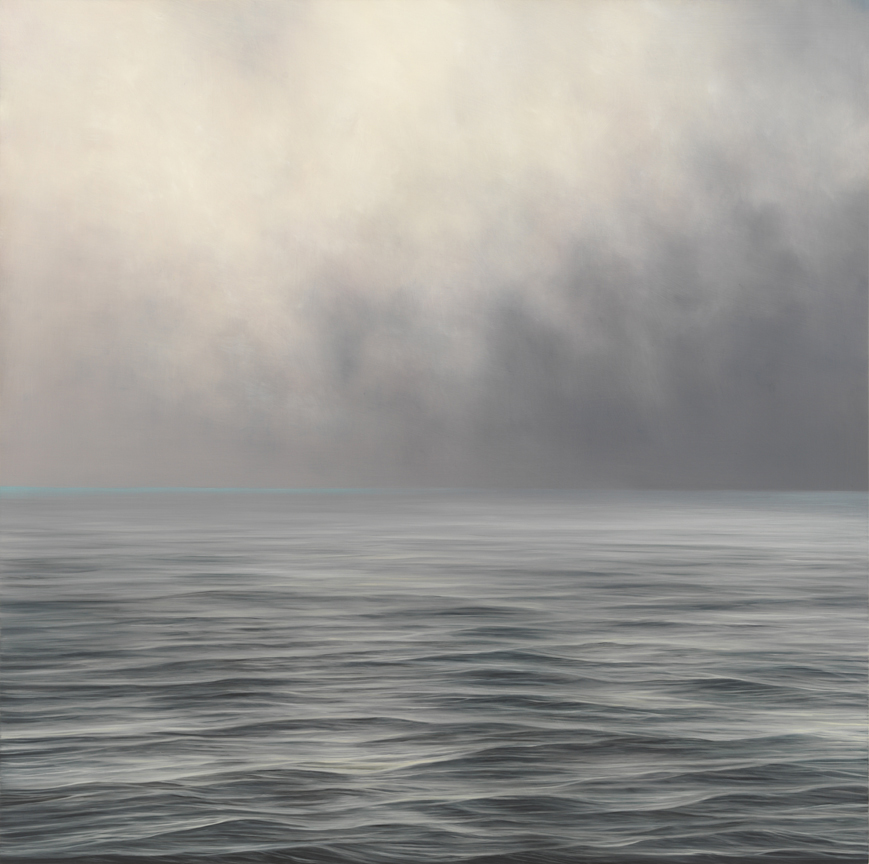

I’ve always loved the feeling of a pencil in my hand. I remember making a drawing of a little girl when I was about five years old. I wanted to decorate her dress, so I drew a zigzag across it. Then I drew another zigzag above it so that the upward points of one zigzag touched the downward points of the other zigzag. I repeated these zigzags until her entire dress was covered. I use similar marks to create waves in my water/sky paintings today–layer upon layer of zigs, zags, and diagonals, the wet paint of one line blending into the wet paint of another.

I was an uneven student in school. If I enjoyed a class, I paid attention. If I was bored, I’d tune out, retreating into my own imagination by drawing in my notebook. It made my body feel good to make marks on paper, to draw scenes of things I wish I were doing instead. Once, when I was in 4th grade, I became so absorbed in my drawing that had no idea we had switched from one subject to another. My teacher called on me, and I had to rocket back to Earth just to look up and say “Huh?” My teacher picked up my notebook full of drawings and, in front of the entire class, demanded to know why I hadn’t been taking notes. It was humiliating. Simultaneously, I felt a fierce justification for my right to draw, even if I was only a child in elementary school.

This was the first time I realized that my artistic drive had a strong will and would not tolerate being told to retreat. I intended to study psychology in college. But I took more art classes than psychology classes, so I switched my major to art. After college, I felt that becoming an artist was impractical, so I decided to apply to graduate schools in psychology. I sat down with my applications to write an essay about why I wanted to become a clinical psychologist. The words would not come. I burst into tears instead. It was as if my strong-willed artist-self picked me up by the scruff of my neck, removed me from that graduate school application, and set me down where it wanted to be: on the path to becoming a painter. I was 24 years old and I realized I would much prefer to put everything I had into my art and fail miserably at it than not try at all.

I applied to MFA programs in painting three times. The first time I didn’t get in anywhere. The second time I got into one program, but I wasn’t excited about it and they didn’t award me a scholarship. I continued to work on my art. The third time I got into Northwestern, with a generous fellowship. My two years at Northwestern were excellent. I studied with exceptional artists whose sensitivity towards images produced in me a resolve to find my own direction as a painter. The other MFA students were brilliant and quirky. Many of them have gone on to have outstanding careers as artists. I met my husband Steve Carrelli in the Northwestern MFA program. It is impossible for me to imagine my life as an artist without him. When we met, we both had the ambition to create the best art we could. We’ve supported each other every step along the way.

I graduated from Northwestern in 1994 at age 30. My education there gave me the confidence to approach galleries and embark upon a twenty-year teaching career at Columbia College Chicago. Since 2013, I’ve worked full time in my own studio, creating paintings to be exhibited and sold in galleries. I credit the unbidden fierceness of my artist-self for my ability to work full time as an artist, the one who, behind the face of an embarrassed 4th grader, snarled at my teacher; the one who plucked me away from embarking upon the wrong (for me) career. I also credit my husband, my parents, my teachers, the galleries and collectors I’ve worked with, and the community of artists around me.

No one can thrive without a network of good people to support them. Yet, no one can embody a vision for another person; that task that belongs to each individual. What we can do, though, is raise each other up with love and support so that we all can thrive.

We’re always bombarded by how great it is to pursue your passion, etc – but we’ve spoken with enough people to know that it’s not always easy. Overall, would you say things have been easy for you?

When I look back on my life as a young artist, I can honestly say that I always had everything I needed. But in my twenties and thirties, I did not know that this would always be the case. In some years, I made less than $10,000 working part-time jobs. I was wracked with worry that I would not be able to pay rent. There was also a time when I had trouble buying health insurance because of a pre-existing condition. I was offended at the thought of having to find a full-time job solely to obtain health insurance. But I would’ve done it had it been necessary for my survival.

I often felt like I was not going to be OK. But I come from a solidly comfortable family, and I knew I had a place to go if I truly hit bottom. On the other hand, my parents made it clear that I had to support myself. They raised my sister and me to be self-reliant and instilled in us a serious work ethic. In retrospect, my struggles as a young artist were not about my personal situation. My struggles were about the negative messages about artists in our culture, and how those messages translate into realities that encumber artists, such as the paucity of grants and teaching jobs that pay a living wage. The most pervasive of these oppressive messages have to do with money and mental health. We are taught that artists are mostly poor, that we are crazy, depressed, and have addictions, and that we belong on the fringes of society.

As much as I wanted to be an artist, I had also internalized these negative messages. So when I struggled with money, I was scared. My fear made me feel depressed, and when you’re depressed, and can rarely spend money to go out, you feel isolated. So I had all of these feelings, a lot. I fought hard not to allow these feelings dictate how I lived my life. What buoyed me was that the possibilities of my art always felt stronger and brighter than the negativity of these feelings. Objectively, things got better when I got into graduate school at Northwestern. I was immersed in a community with other artists, I had a fellowship, and I fell in love with my husband. When I graduated, I found an adjunct teaching job and gallery representation in Chicago right away. With Steve’s and my combined incomes, we were more financially stable, but money was still tight for many years.

After graduate school, I still struggled with fear that my world would collapse and I would fail as an artist. I cried a lot because of it. Oh, the tears! I think anyone engaged in an authentic and unique creative practice experiences fear. It expresses itself differently in different people. Fortunately, I had a close friend, not an artist himself, who would ask me if anything was preventing me from painting that day. My answer was usually no, so he would remind me that on this day there was nothing preventing me from living my life fully as an artist. Just like that, day by day, I built a life as an artist.

So let’s switch gears a bit and go into the Louise LeBourgeois story. Tell us more about the business.

I am most known for my water and sky paintings.

At Northwestern, I became frustrated with the way I painted. Because I saw Lake Michigan every day, I thought it would be a good subject to use to practice my painting skills. I thought that if I could paint water, which is in constant motion and both transparent and reflective, then I could paint anything. It began as an exercise, then evolved into an obsession. I jettisoned the solid forms of landscape for the ever-shifting water and vaporous sky as a way to frame the perfectly visible, yet non-existent, space of the horizon line.

I am also a swimmer. I swam competitively as a teenager, and as an adult, I became an open water swimmer. Water holds contradictions. It is both yielding and resistant, and swimmers make use of both these qualities to move through the water. I’ve always loved the feeling of water’s resistance and acquiescence at the same time, and I’ve always loved looking at light refracted through water. The hours I spend swimming in Lake Michigan provide me with ample visual material to bring to my art.

Water, light, and the horizon line are playful entities that toy with our human desire for certainty. But the contradictory, slippery, defiant frolic of water, light, and horizon keep me enthralled. Paint, as a substance, is also slippery and defiant. Painting can be a real slog, so when I’m up to my ears in oily paint and trickster subject matter, it’s always thrilling when an image starts to coalesce. I make paintings, actual physical objects, yes. But I aim for the intangible in my art because that’s where our souls reside.

How can people find your art?

I show at the following galleries:

Dolby Chadwick Gallery in San Francisco

Gold Gallery in Boston

Gallatin River Gallery in Big Sky, Montana

In Chicago, I participate in group shows, most recently at Addington Gallery. I occasionally hold an open studio, and I am available for commissions. I have a permanent installation of my images at Chicago’s 17th District Police Station at 4650 North Pulaski. The paintings on paper which were my proposal for this installation are on display on the 4th floor of Chicago Cultural Center at 78 East Washington.

I also have a new website through which collectors can order prints of some of my paintings: store.louiselebourgeois.com

Has luck played a meaningful role in your life and business?

I think of good luck as the advantages we’ve been given with no effort on our part. I think the opportunities that come our way because of work we’ve already done are due to our own sweat and effort. But the two are related. My family primed me to become an artist.

My father was a history professor who painted as a hobby and still does. My mother loves art and has a strong visual sensibility. I learned that paintings had significance. I am also lucky to have been born when I was, in the overlap between the Baby Boomers and Generation X. College tuition was not onerous when I attended, and my parents were able to pay for my education. I graduated without student loan debt.

Also lucky was that Steve and I were of an age to buy a home before housing prices started to explode. In 1998, we bought a large condominium in Rogers Park that needed a lot of work, but it cost less than $100K. Our parents helped with the down payment. Steve and his father gutted and rebuilt the kitchen. Our mortgage payments were less than the rent we had been paying. We still live in the same condo, which means our housing costs have been low for many years.

The fact that I’ve lived my adult life with very little debt has meant that I’ve had more time to make art. It was my own decision to live frugally and focus on painting, but the socio-economic class and generation I was born into was random luck, and it absolutely helped me.

I’ve had opportunities and rejections. Both have come because I put my work out into the world. In general, persistence attracts opportunity. It might look like good luck from a distance, but in the arts, it always contains a backstory of resolve and hard work.

There’s grace too—when you get that grant, or you meet exactly the right person, or a possibility you could not have imagined presents itself. You’ve set the stage and magic appears.

Louise LeBourgeois | Mellifluous Morning #581, 2018 | Oil on panel | 12 x 12 inches